How Suddenly will AI Accelerate the Pace of AI progress?

Released on 17th March 2025

Citations

This is a rough research note – we’re sharing it for feedback and to spark discussion. We’re less confident in its methods and conclusions.

Today, AI progress is driven by humans, who write software and design and produce AI chips. But in the future, more and more human work will become automated. Eventually, AI progress will be driven by AI, not humans.

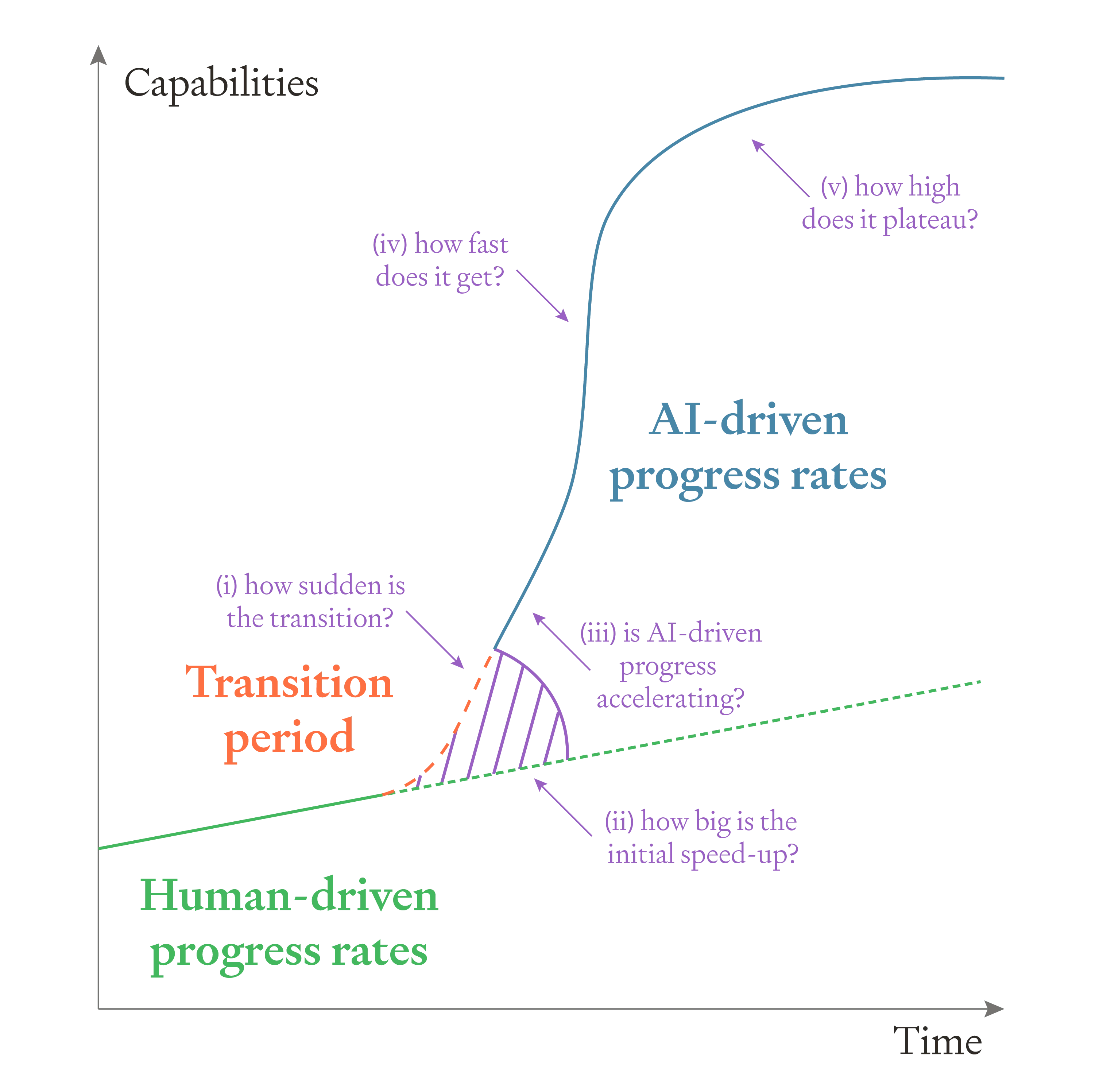

What might the transition from human-driven to AI-driven progress look like? We can imagine a graph which plots AI capabilities over time:

Image

In the graph, AI progress is initially driven by human efforts (green line). Then, over time, AI increasingly automates the work of improving AI (orange line). Eventually, AI does almost all the work of improving AI (blue line). There is a continuous transition from today’s era of human-driven progress to a future era of AI-driven progress.

The graph raises several different factors that are relevant to understanding the landscape of the transition to AI-driven progress:

(i) Suddenness: how many months or years does it take to transition from human to AI-driven progress?

(ii) Initial speed-up: how much faster is the initial period of AI-driven progress compared to the final period of human-driven progress?

(iii) Acceleration: after the transition, will AI-driven progress accelerate over time?

(iv) Peak growth rate: how fast could AI progress eventually become?

(v) Plateau: how far can AI progress before hitting effective physical limits?

(i) Suddenness: how many months or years does it take to transition from human to AI-driven progress?

(ii) Initial speed-up: how much faster is the initial period of AI-driven progress compared to the final period of human-driven progress?

(iii) Acceleration: after the transition, will AI-driven progress accelerate over time?

(iv) Peak growth rate: how fast could AI progress eventually become?

(v) Plateau: how far can AI progress before hitting effective physical limits?

(i) and (ii) happen during the transition period; (iii)-(v) happen during the era of AI-driven growth.

How should we define when the transition period starts and ends?

We can think about this period in terms of the elasticity of AI R&D output from humans and AI for each feedback loop: how much the marginal pace of progress increases if you increase the population of humans or AIs by 1%. We can say that the transition period begins when AI elasticity is first >1/10 that of human labor and ends when it’s >9/10. The specific start and end points are arbitrary, but for any such choice, there’s a wide range of possibilities for:

- How sudden the transition period could be: it could take anything from months to decades.

- How fast the initial speed-up from AI-driven progress could be: the pace of AI progress could increase by 2X or 100X over the course of the transition.

This post explores the dynamics of this transition by analyzing (i) and (ii).

The transition will likely play out differently in different areas of AI progress. We think it’s helpful to distinguish between three separate feedback loops in which AI improves AI:

- A software feedback loop, where AI develops better software. Software includes AI training algorithms, post-training enhancements, ways to leverage runtime compute (like o1), synthetic data, and any other non-compute improvements.

- A chip technology feedback loop, where AI designs better computer chips. Chip technology includes all the cognitive research and design work done by NVIDIA, TSMC, ASML, and other semiconductor companies.

- A chip production feedback loop, where AI and robots build more computer chips.

We argue that the transition from human-driven to AI-driven progress has the potential to be the most sudden and biggest for software, followed by chip technology and then chip production.

Suddenness

How sudden could the transition from human-driven to AI-driven progress be?

Image

Time lags

One reason things are unlikely to be extremely sudden is that all the feedback loops have inbuilt time lags.

Image

Software has the shortest time lags, and chip production probably has the longest:

- It takes ~3 months to train new SOTA AI, which is the main time lag in the software feedback loop (though post-training enhancements, such as fine-tuning, take much less time).

- For the chip technology feedback loop, it’s also necessary to integrate new technology into chip factories and print a stock of new chips, which would take many months.1

- It takes years to build new fabs, which would be needed for the chip production feedback loop.

We can subdivide the three feedback loops further and visualize the duration of the time lags for each subdivision.

Image

Gradual automation

Another reason is that tasks for each feedback loop won’t be automated all at once, but gradually. The more gradual the automation, the less sudden the transition.

Automation will be more gradual where:

- The tasks to automate are varied, so we gradually automate more and more of them (rather than automating all tasks at once).

- There isn’t already data on the tasks, so data needs to be collected in the physical world.

- The tasks take a long time, and so gathering data takes longer. Tasks in the physical world will tend to take longer and sometimes much longer than virtual tasks.

These considerations suggest that software automation will be more sudden than the automation of chip technology and chip production:

- The tasks are less wide-ranging.

- There’s much more online data (and easy access to data in the heads of human experts who already work at the relevant companies).

- The tasks are entirely virtual.

The automation of chip technology would likely be less sudden than software but more sudden than chip production:

- According to our definition, chip technology tasks are also entirely virtual, in contrast to chip production tasks, which are predominantly physical.

- But there’s much less online data for chip technology than for software, and the tasks are more varied.

Rapid AI progress

The software feedback loop is likely to happen first.2 If the software feedback loop leads to a large and rapid increase in capabilities, then automation of other areas could happen very suddenly, and the time lags in other areas (e.g. time to print chips) could be reduced. That could mean the chip technology and chip production feedback loops begin very suddenly.

Initial speed-up from AI automation

As well as considering how sudden the transition from human-driven progress to AI-driven progress might be in calendar time, we can also ask how much faster AI-driven progress will initially be compared to human-driven growth.

Image

For the software feedback loop, the initial speed-up from automation could be very large. Currently, frontier labs have only a few hundred people working on software R&D, but once AI can automate these jobs, that number could quickly rise to millions of human-equivalent software R&D workers. This gain won’t be bottlenecked by physical constraints like constructing fabs and printing chips, though it would be limited by the time taken to run AI experiments and train new models. Estimates of the size of the initial speed-up from automating software vary from 2x to 20x faster progress than pre-automation, though they are very speculative.3

The initial speed-up for the chip technology feedback loop is highly uncertain. The innovations that could be incorporated most quickly are probably in chip design. Interviewees from this chip design report were asked how much AI might speed up progress. They thought that:

- A narrow AI chip designer that thought 100x as fast as human designers might increase FLOP/$ by 1.5-4X over the next year, increasing the pace of hardware progress by 2X-4X.

- A ‘perfect’ GPU design might increase FLOP/$ by 10X-100X or more. If this happened very quickly over 2 years, that would be a speed-up of 4X-14X.

| Capability level | Time period | FLOP/$ increase | Increase in the pace of hardware progress |

|---|---|---|---|

| Narrow AI chip designer, 100X human speed | 1 year | 1.5-4X | 2X-4X |

| A perfect GPU design | 2 years | 10X-100X | 4X-14X |

Including other types of chip technology innovation beyond chip design would increase this factor, but their effect would be limited by the time it takes to make new machines and fabs.

The chip production feedback loop would probably have the smallest initial speed-up:

- It takes years to build new fabs, so initial gains will be limited.

- Just before this feedback loop kicks in, the growth in the number of chips being used for training might already be very high, which would mean that it would be hard to increase that growth rate much further.

- Specifically, this pre-chip-production-feedback growth might happen via an unsustainable route: we might simply increase the proportion of chips used in AI training. But you can only increase this percentage up to 100%, and beyond that point, you need to build more fabs.

Conclusion

There will really be multiple gradual transitions from human-driven to AI-driven progress as different domains of progress transition at different times.

The transition from human-driven to AI-driven progress has the potential to be the most sudden and biggest for software (especially for post-training enhancements), followed by chip technology and then chip production.

Thanks to Max Dalton, Oscar Delaney and the governing explosive growth seminar group for helpful comments.

Footnotes

Released on 17th March 2025