Intelsat as a Model for International AGI Governance

Released on 13th March 2025

Citations

Abstract

If there is an international project to build artificial general intelligence (“AGI”), how should it be designed? Existing scholarship has looked to historical models for inspiration, often suggesting the Manhattan Project or CERN as the closest analogues. But AGI is a fundamentally general-purpose technology, and is likely to be used primarily for commercial purposes rather than military or scientific ones.

This report presents an under-discussed alternative: Intelsat, an international organization founded to establish and own the global satellite communications system. We show that Intelsat is proof of concept that a multilateral project to build a commercially and strategically important technology is possible and can achieve intended objectives—providing major benefits to both the US and its allies compared to the US acting alone. We conclude that ‘Intelsat for AGI’ is a valuable complement to existing models of AGI governance.

Executive summary

The International Telecommunications Satellite Organization (Intelsat) is an international organization which established and managed the global satellite communications network. Before being privatized in 2001, Intelsat was governed by member states with voting rights based on system usage. It was managed for its first 15 years by Comsat, a private company which the USG established for this purpose. Intelsat members invested capital and paid charges for usage, and received returns on their investments, satellite service, and access to technical information. The technology development itself was competitively contracted out to external companies.

The history of Intelsat

Intelsat was founded in the 1960s as part of the US’s wider attempt to win hearts and minds away from the USSR. The 1962 Communications Satellite Act set up the Communications Satellite Corporation (Comsat) with a mandate to work with other nations to set up a global satellite system. In 1964 the US, European nations, Canada, Japan and Australia signed interim agreements forming Intelsat, an international organization to own and manage the system. The US had 60.1% of the voting shares, but supermajorities were required for important decisions. The price of fast interim agreements which were favorable to the US was a commitment to renegotiate definitive agreements later.

Intelsat’s first satellite was launched in 1965 and it achieved global coverage in 1969, in time for the broadcast of the moon landing. In 1969, negotiations began for the definitive agreements, which took effect in 1973. In the 1970s, Intelsat began to compete with domestic systems, in the 1980s with regional systems, and in the 1990s with fiber-optic cables. Under pressure from competition and without the Cold War dynamics that had initially motivated the US, Intelsat was privatized in 2001.

Intelsat as a model for AGI governance

We define artificial general intelligence (“AGI”) as an AI model, or collection of models, that performs as well as the most capable humans at essentially all economically relevant cognitive tasks. We believe that early Intelsat is a promising model for international AGI governance, and serves as a valuable complement to existing models like the Manhattan Project or CERN, for two main reasons:

- First, Intelsat is proof of concept that a multilateral project to build a commercially and strategically important technology is possible and can achieve intended objectives.

- Second, Intelsat shows that a multilateral project can provide major benefits to both the US and its allies compared to the US acting alone.

Any feasible model for international AGI governance needs to be desirable from a US perspective. We think that Intelsat is a particularly feasible model which balances US national interest with meaningful international involvement. The history of early Intelsat suggests that:

- Weighted voting with supermajorities for important decisions can be politically feasible, giving the US primary control while providing a meaningful say to allies.

- Interim agreements with an initially small number of allies can allow agreements to be set up relatively quickly.

Intelsat also demonstrates that the formation of a multilateral project provides an opportunity to desirably shape the trajectory that a new technology takes.

There are important disanalogies between communication satellites and AGI. The stakes are higher for AGI development, with greater potential benefits and more important military applications. The balance of power between the actors involved is also different: governments were more involved in the development of satellite communications technology than they have been so far in AGI development, and the US depends more heavily on allies for the development of AGI than it did for satellite communications.

We don’t think these disanalogies undermine Intelsat as a useful model for a multilateral AGI project; in some cases, they make the model more appropriate, rather than less.

We don’t claim that a multilateral project to build AGI is the right approach to AGI governance, nor do we claim that the Intelsat model is clearly superior to models such as CERN or the Manhattan Project. But we hope that Intelsat becomes one of the models that is considered for international AGI development. Future work might explore whether a multilateral AGI project is desirable or not, and flesh out the implementation details (membership, voting shares, benefit sharing, enforcement) for an Intelsat for AGI.

Overview of Intelsat

The first satellites were launched in the late 1950s. In the early 1960s, the USG became committed to a USG-led global satellite communications system. The US wanted a victory in the space race and in the wider struggle for hearts and minds with the USSR, and to prevent an AT&T monopoly (which would undermine these soft power objectives).1 The 1962 Communications Satellite Act established the Communications Satellite Corporation (Comsat) with a mandate to work with other nations to set up a global satellite communications system. | |

International negotiations then began, and in 1964 the US, European nations, Canada, Japan and Australia signed interim agreements forming Intelsat, an international organization to own and manage a global satellite communications system. The US preferred negotiating with a smaller group for speed, and expected developing nations to be easily persuaded to US terms. The price of fast interim agreements which were favorable to the US was a commitment to renegotiate definitive agreements later, which were expected to be less favorable.2 Intelsat’s first satellite was launched in 1965, and it achieved coverage of all continents in 1969, in time for the broadcast of the moon landing. | |

In 1969, negotiations began for the definitive agreements, which took effect in 1973. Under the definitive agreements, US influence decreased significantly: Comsat lost the management of the system,3 US vote share was capped at 40%, and regional systems became more acceptable. | |

In 1971, the USSR launched a rival system, Intersputnik, but it remained small.4 In the 1970s, Intelsat began to compete with domestic systems, in the 1980s with regional systems, and in the 1990s with fiber-optic cables.5 In 2001, Intelsat was privatized, under pressure from competition and without the Cold War dynamics that had initially motivated the US. |

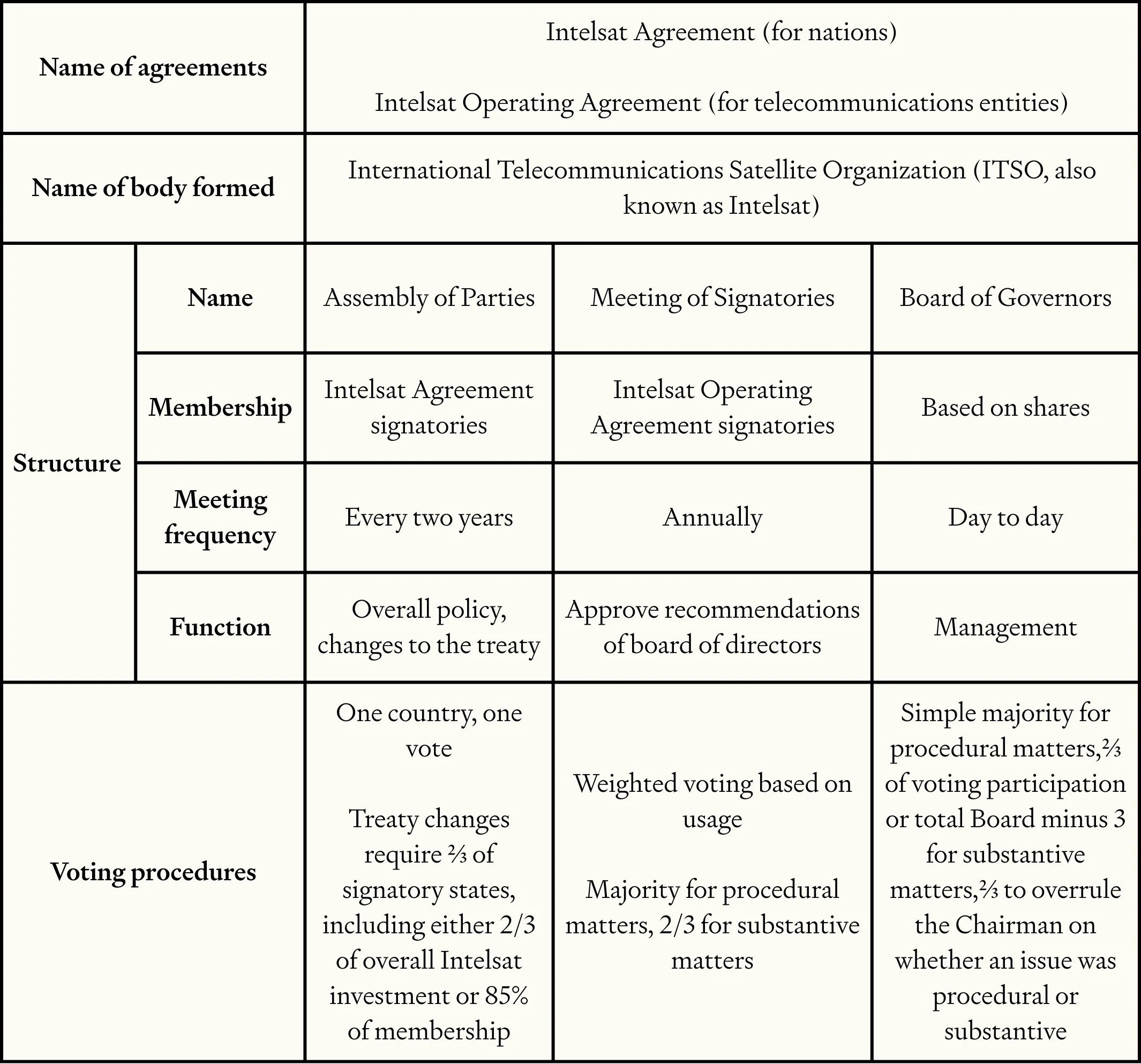

Table 1: Overview of Intelsat

The origins of Intelsat

The USSR launched the first satellite, Sputnik, in 1957. But the US had the lead in communications satellite technology, launching the first communications satellite, SCORE, in 1958.

Communication satellite technology in particular was seen to be important in several ways:

- Commercially, it was expected that communications satellites would complement and expand the telecommunications market in general (both for telephony and eventually television). This was expected to be very lucrative.6

- Geopolitically, communication satellites were seen as an important part of the war for hearts and minds between the US and the USSR. Achieving technical milestones first was part of the space race for prestige. A deployed global satellite system would also strongly influence what media and propaganda was available in developing nations.7

- Militarily, satellite communications were attractive as a more reliable form of communication than electronic communications, particularly in remote areas - and one which might remain operational even in the event of a nuclear strike on ground stations, unlike radio networks.8 Launchers for communication satellites could also be used to launch ICBMs, so control of this aspect of the technology was militarily significant.9

In the early 1960s, the USG became committed to a USG-led global satellite communications system.

The first call for the government to create a global system was made in autumn 1960, in a staff report commissioned by Lyndon Johnson.10 The stated reason for a global system was national security interests, particularly in terms of soft power. Two days after Gagarin became the first man in space, in April 1961, Kennedy asked aides what could be done to win the space race.11 The response was another report submitted by Lyndon Johnson, recommending the moon landing and a global satellite communication system. Kennedy accepted the report with few changes,12 and announced the plans in a speech to Congress in May.13

There followed a series of debates on the Space Council during 1961, to decide how to set up the global satellite system. The DoD preferred private ownership because otherwise legislation would be required which it feared would take longer. The State Department wanted public ownership so that it could negotiate with foreign powers and because it thought this would look better internationally; the DoJ preferred public ownership because of concerns about monopoly. In the end it was decided to go down a legislative route and set up a state-influenced private company.14

The 1962 Communications Satellite Act established the Communications Satellite Corporation (Comsat) with a mandate to work with other nations to set up a global satellite communications system. Comsat shares were divided equally between common carriers and the general public. Of the 15 members of the Board of Directors, six represented international carriers, six represented the general public, and three were appointed by the President.15

The USG became committed to an international project for communications satellites for three main reasons.16 First, the USG wanted a quick victory in the space race.17 The US was behind in the space race, but ahead in communication satellite technology.18

Second, the USG wanted to be the first to deploy communications satellites to developing nations, in order to:

- Prevent them from becoming communist,19

- Spread American culture and soft power, and20

- Win developing economies away from former colonial powers.21

Third, the USG believed that the counterfactual was an AT&T owned monopoly, using nonsynchronous, medium-altitude satellites and serving developed nations only (see below).22 This was seen as undesirable because:

- It would undermine US soft power goals.

- The State Department wanted USG involvement in international negotiations, rather than having companies negotiate directly on a geopolitically important issue.23

- It was militarily preferable to have a geosynchronous system with simple, portable ground stations and wide coverage.24

- There were general sentiments against monopoly.25

The interim agreements

International negotiations began after the Communication Satellite Act in August 1962. In 1964 the US, European nations, Canada, Japan and Australia signed interim agreements forming Intelsat, an international organization to own and manage a global satellite communications system.

Members invested capital and paid charges for usage, in return for:

- Satellite service,

- Returns on capital investments,

- Contracts in proportion to investment, if and only if price and quality were competitive,26

- Free access to all inventions, technical data and information; and27

- The right to own and operate their own earth stations.28

Name of agreement | Agreement Establishing Interim Agreements for a Global Communications Satellite System |

|---|---|

Name of body formed | Interim Communications Satellite Committee (ICSC) |

Structure | Executive: ICSC Management: Comsat |

Voting procedures (ICSC) | Weighted voting based on usage (US 60.1% of voting share with a guaranteed minimum of 50.5%) Supermajorities required for important decisions: - US votes plus 12.5% - US votes plus 8.5% if no agreement after 60 days, on a subset of important decisions Most decisions were in fact made unanimously29 |

Table 2: The interim agreements

Comsat managed the system, which was governed by the Interim Communications Satellite Committee (ICSC, also known as Intelsat).

Voting shares were based on usage, which was initially determined using estimates based on international telephone traffic. As the largest user of international telephony, the US started out with 60.1% of Intelsat votes.30 This share decreased as new members joined, but total votes for new members were capped at 17%, and the votes of all founding states decreased proportionally.31 This ensured that the US voting share could never fall below 50.5%, and so gave the US a guaranteed veto.32

A group of fourteen important decisions required 12.5% of votes in addition to the US, which meant that at least some European votes were required.33 For a subset of these decisions - on space segments, budget, contracts and launches - this reduced to 8.5% in addition to US votes, if no agreement had been reached after 60 days.34 This prevented the Europeans from permanently blocking something (Canada, Australia and Japan’s combined voting share was 8.5%), but meant that the US would still need some allied support.

Comsat competitively contracted out the actual technology development to other companies.

Intelsat’s first satellite was launched in 1965, and it achieved coverage of all continents in 1969, in time for the broadcast of the moon landing.

Note that this report focuses on the early history of Intelsat, and does not consider later developments in detail.

The definitive agreements

In 1969 negotiations began for the definitive agreements, which came into force in 1973.

The negotiations35

The interim agreements required the USG to convene negotiations for definitive agreements.36 The definitive agreements must:

- Follow the principles of the interim agreements (including the commitment to a single global satellite system open to all states),

- Be open to all states who were members of the ITU,

- Safeguard the investment of signatories, and

- Allow all parties to the definitive agreements to contribute to the determination of policy.

As mandated by the interim agreements, the ICSC submitted a report in December 1968, outlining the alternatives.37

The USG convened the first plenipotentiary conference from February 24 to March 21, 1969, with delegations from Intelsat and observer nations. The conference’s first actions were to establish an agenda and formal procedures for making decisions.38

The first conference established a Preparatory Committee to reduce the number of alternative proposals.39 The preparatory committee met three times in 1969, and the second plenipotentiary conference was held from February 16 and March 20, 1970. Japan and Australia submitted a promising compromise proposal, and an International Working Group was established to draft an agreement based on the proposal.40 The IWG met throughout 1970, and the final plenipotentiary conference began on April 14, 1971. A two-thirds majority was required to amend any unresolved parts of the agreements.41 The text was agreed in May, and opened for signature in August 1971. By December 1972, two thirds of members had signed the definitive agreements, which took effect in February 1973.

The agreements

Under the definitive agreements, the US lost its dominant position, as it expected to. The main differences between the interim agreements and the definitive agreements were:

- Management passed from Comsat to Intelsat, with a transition period until 1979.

- The US vote share was capped at 40%, regardless of usage.

- Regional systems became more acceptable.42 Under the interim agreements, these had been disallowed, and the US proposed that this continue under the definitive agreements. In the end, the definitive agreements continued to use the rhetoric of a single system, but included a procedure for setting up separate systems.43

Image

Table 3: The definitive agreements

Later history

In 1971, the USSR launched a rival system, Intersputnik, but it remained small.50

In the 1970s, Intelsat began to compete with domestic systems, and in the 1980s with regional systems (especially EUTELSAT, ArabSat and Papapa). In the 1990s Intelsat lost point-to-point voice communication to fiber-optic cables, and began to focus on other services, especially in regions without cables.51

In 2001, Intelsat was privatized, largely because developed nations no longer supported it:52

- Competition in developed countries forced Intelsat to lower prices. Rules against price discrimination meant that this happened in developing countries too, where prices would otherwise have been much higher.

- For the US, the end of the Cold War significantly reduced the importance of winning hearts and minds through satellite communications.

Lessons for multilateral AGI projects

Proof of concept

Intelsat is proof of concept that a multilateral project to build a commercially and strategically important technology is possible and can achieve intended objectives.

Communication satellites were a primarily commercial technology (militaries set up their own separate systems). But they were also strategically important. In the short term, being the first to set up a communications satellite system would be an important victory in the space race.53 Setting up a global communications satellite system in particular would be a propaganda victory among developing nations.54 In the longer term, whoever provided communications satellites to non-aligned nations would have a lot of cultural influence over those nations.55 There was also the potential to win developing economies away from former colonial powers.56

It was because of the strategic importance of satellite communications, and not in spite of it, that the US chose to go down the multilateral route (see above).

Moreover, early Intelsat broadly achieved its intended objectives:57

- Intelsat achieved global satellite coverage in 1969, just five years after its establishment.

- The USSR’s rival system, Intersputnik, was only set up in 1971 and remained tiny compared to Intelsat.58

- Intelsat itself maintained a near-monopoly in international communication satellites for over a decade.59

- US soft power over developing nations did become quite pervasive: many developing nations joined Intelsat, and the influence of American media and culture globally has been very significant.60

Like communication satellites, AGI has strong commercial and strategic significance. Intelsat demonstrates that a multilateral project to build a commercially and strategically important technology is possible and can achieve intended objectives.

Benefits of a multilateral project over acting alone

A multilateral project can provide major benefits to both the US and its allies compared to the US acting alone.

The US had the technology and resources to set up a satellite communications system unilaterally. Their technological lead was substantial.61 Comsat raised $200m ($2b in today’s money) in its IPO and was oversubscribed.62 It had already contracted Intelsat’s first satellite before the interim agreements.63

But in spite of this dominant position, the US unilaterally committed to setting up a global satellite communications system in collaboration with other countries. There was no substantial pressure from international partners for the US to do this. The US didn't consult international partners before committing to this approach, and didn’t have a serious plan for how a multilateral project would work until after they had committed to it.64

The reason that the US behaved in this way is that there were major benefits to the US from a multilateral project compared to acting alone. A large part of the US motivation for Intelsat was to win a propaganda victory over the USSR, by collaboratively setting up a global satellite system serving developing countries (see above). This goal would have been undermined if the US had imposed a system unilaterally. And ultimately foreign nations would have to either build ground stations or allow US parties to build them, so some degree of negotiation and consent was inevitable.65

A multilateral project also provided obvious benefits to allies compared to the US acting alone. The main benefits to European allies were access to the underlying technology, and a say in the governance of the global satellite system. Initially, European powers considered threatening to set up a rival system, but realized that this was impossible given the state of European technology. They therefore decided to negotiate with the US for the best deal they could get.66

In the case of AGI, a multilateral project may be even more beneficial, compared with the US acting alone, than it was in the case of satellite communications. Possible benefits to the US of a multilateral AGI project include: Better access to allied talent and resources. This probably holds more strongly for AGI than it did for satellites (see below). Increased influence over future AI development and deployment. This could be important both in terms of safety and security, and in terms of economic gains. Greater legitimacy, and potentially greater market power. International governance would probably make US AGI development more legitimate in the eyes of its close allies and other nations. For allied nations, a multilateral project for AGI would increase access to cutting-edge AI technology, and increase influence over AGI development and its governance.

Weighted voting with supermajorities for important decisions

Weighted voting with supermajorities for important decisions can be politically feasible, giving the US primary control while providing meaningful influence to allies.

The US maintained substantial control under Intelsat’s interim agreements through weighted voting. Voting shares were based on usage, which was initially determined using estimates based on international telephone traffic. The US was the largest user of international telephony. Moreover, domestic telephone traffic over two thousand kilometers also counted, which further inflated the US share (because of Guam, Hawaii and Puerto Rico).67 The US therefore started out with 60.1% of Intelsat votes.68 This share decreased as new members joined, but total votes for new members were capped at 17%, and the votes of all founding states decreased proportionally.69 This ensured that the US voting share could never fall below 50.5%, and so gave the US a guaranteed veto.70

However, even under the interim agreements, allies retained some influence via supermajority rules. A group of fourteen important decisions required 12.5% of votes in addition to the US, which meant that at least some European votes were required.71 For a subset of these decisions - on space segments, budget, contracts and launches72 - this reduced to 8.5% in addition to US votes, if no agreement had been reached after 60 days. This prevented the Europeans from permanently blocking something (as the combined voting share of Canada, Australia and Japan was 8.5%), but meant that the US would still need some allied support.

As with satellite communications, the US is technologically leading in AGI development, and will probably seek to preserve a dominant position in any multilateral project. Intelsat suggests that weighted voting with supermajorities may be a plausible model for AGI governance, preserving US dominance while enabling allied influence.

Agreements can be set up quickly

Interim agreements with an initially small number of allies can allow agreements to be set up relatively quickly.

Intelsat was set up relatively quickly (see Table 4). There were only eight years between the first public commitment and the achievement of global coverage. Moreover, setting up Intelsat as an international organization only took two years. There had been no discussion with other countries prior to the Communication Satellite Act in August 1962,73 and little thought on the US side about the nature of any international arrangements.74

May 1961 | First public commitment to a global satellite communications system |

August 1962 | Legal commitment to a global system via the Communication Satellite Act |

August 1964 | Intelsat’s interim agreements signed |

April 1965 | Launch of Early Bird, Intelsat’s first satellite |

1969 | Intelsat achieves global coverage |

Table 4: Key dates in Intelsat’s establishment

It was possible to make the Intelsat agreements quickly for three main reasons.

First, the US was motivated to make an agreement quickly, for several reasons:

- The US wanted a quick victory in the space race, which they were losing. Two days after the first manned space flight, Kennedy asked aides what could be done to win the space race.75 One of the suggestions he accepted was a global satellite network.

- The US wanted to preempt an AT&T monopoly serving only the developed world. AT&T had informed the FCC that it wanted to build a global system in summer 1960, and was leading in various important aspects of communication satellite technology.76

- The US wanted to set up Intelsat before new transatlantic cables were laid, which might undermine the commercial viability of Intelsat. There were plans to greatly expand cable capacity by 1966. The USG put pressure on AT&T to inform European partners that it would prefer satellite technology over new cables where either were practicable.77

The US also wanted to deploy communications satellites to developing nations before the USSR did, but this likely wasn’t a major factor. The USSR lagged behind the US in satellite communications technology, and the US knew this.78 The USSR also didn’t have a strong incentive to build an international system, as most of its long-range communications were domestic.79 In the end, the USSR didn’t set up its rival system, Intersputnik, until 1971.

Speed is also important for the establishment of a multilateral project for AGI:80

- If AGI is developed within the next 5 years, there will be limited time to establish such a project.

- Whether or not AGI is near, speed might be important to ensure that a multilateral project is in place before any less desirable alternatives.

Importance of speed for a multilateral AGI project

Second, the agreements were negotiated between an initially small number of allies. Within a month of the Communication Satellite Act, the USG had already decided not to involve the UN or developing nations in negotiations.81 There were a few reasons for this:

- The US feared that the USSR might deliberately delay UN negotiations, as it didn’t have strong incentives for an international system.82

- It was expected that most opposition would come from European nations, who wanted to protect their colonial cable and radio networks. The US wanted to negotiate directly with these powers to find agreement.84 Note that the US also demanded the inclusion of Japan, Canada and Australia in the negotiations, as a counterweight to the European bloc.85

A multilateral project for AGI is likely to be much more feasible if it comprises only a small number of allies:

- Negotiations are likely to be faster with a smaller group.

- Running the project itself is likely to be easier with a smaller group, because:

- Decision costs will be lower.

- Restrictions on the transfer of information might apply to larger groups, via export controls, ITAR or other means.86

On the other hand, including China and other AGI competitors could reduce international racing and the risk of war.

One approach to balancing these concerns would be to negotiate initially with a small number of founding members who have full technological access, and later offer non-founding membership with more limited access to a broader set of actors.

Size of membership for a multilateral AGI project

The initial number of negotiating parties was small because the US chose to negotiate with a small number of nations. But in practice the number was even smaller, because the European nations negotiated en bloc, to increase their bargaining power. This was faster than bilateral negotiation, and so was overall preferable to the US.87

Third, Intelsat was initially set up under interim agreements, and so disagreements could be delayed to a later date. The interim agreements specified that definitive arrangements would be made, that they would be open to all states, and that all parties to the definitive agreements would contribute to the determination of policy.88 Committing to definitive arrangements later was largely a concession to Europe. All parties expected that US technological dominance would decrease over time, such that the European bargaining position would be stronger later. When negotiating the interim agreements, the US negotiating party expected that the price of control over the interim agreements would be promises about the definitive agreements. They sought to extend the interim agreements for as long as possible, to make the most of their technological monopoly while they had it.89

In the case of satellite communications, the US was willing to trade long-term influence for speed and short-term influence. The US believed that there would be important early decisions to make (particularly on the type of satellite used, and whether this was suitable for global coverage and the US’ soft power goals; see above). Having a lot of short term influence (see above) would allow the US to choose the best system for US national interests. Influence thereafter was less important.

It is possible that a similar dynamic could hold with AGI development, where the US might be willing to trade high influence over important early decisions, for a lessening of influence thereafter. On the other hand, if US dominance increases over time, the US may be less willing to make this trade.

Interim agreements for a multilateral AGI project

Intelsat demonstrates that it is possible to set up important multilateral agreements quickly. To the extent that it is desirable to set up a multilateral AGI project quickly, Intelsat suggests that it may be important to negotiate with a small number of allies, and to negotiate for interim agreements first.

An opportunity for differential technological development

The formation of a multilateral project is an opportunity to desirably shape the trajectory that a new technology takes.

If the USG hadn’t pursued an international project for satellite communications, the likely counterfactual was an AT&T-owned monopoly, using nonsynchronous, medium-altitude satellites.90 In the 1950s and 1960s, AT&T owned most domestic telephone service and almost all international telephony originating in the US.91 Some of the most important early communication satellite research was by AT&T.92 In summer 1960, AT&T informed the FCC of plans to develop a global satellite system.

The technology for nonsynchronous, medium-altitude satellites was more developed than for geosynchronous satellites, and allowing AT&T to build its network would probably have been the fastest way to an international (though not a global) system.93

But an AT&T satellite communications network was seen to be against US national interests in several ways:

- The USG wanted a system which covered the developing world, to increase its soft power. They thought an AT&T system wouldn’t provide this, because:

- Traditionally, AT&T negotiated directly with foreign governments. NASA and the State Department thought the federal government should oversee negotiations with foreign states about the global system, given its geopolitical importance and the US desire for a propaganda victory.96

- The military wanted a geostationary system for deployment situations. DoD wanted to use the civilian network for all but classified communication, and preferred the simple and potentially portable ground stations which geostationary satellites would come with.97

Under Intelsat, the USG successfully pushed for a geostationary satellite system instead of a non-synchronous one.

It is not yet clear what kinds of AI applications will predominate, and we have some influence over which kinds are developed and deployed. An Intelsat for AI could promote beneficial and safe applications, through a mixture of funding, market creation, and prohibitions on unsafe applications.

Disanalogies with AGI

Size of benefits

Benefits from AGI could be much larger than those from satellite communications.

The satellite communications market is estimated to be worth around $23 billion today, while the AI market is estimated to be worth over $600 billion.100 AGI systems (which can perform all human tasks) could (by definition) perform all types of work, which would be an enormous market size. And if AGI triggers explosive growth, then the returns on capital investment might be unprecedented.101

Larger benefits could make allied states more likely to join an Intelsat for AGI, even on terms which are favorable to the US: it is easier to reach agreement if a small fraction of the benefits is worth an enormous amount.102

Potentially very large benefits also make broad benefit-sharing more desirable, to reduce inequality and preserve stability. An Intelsat for AGI might need to consider benefit sharing with:103

- Non-members (so that member states don’t become overwhelmingly dominant over non-member states, particularly nuclear non-member states), and

- Different actors within member states (so that governments or particular government agencies don’t become overwhelmingly dominant over other domestic actors).

Larger benefits from AGI might make it easier to reach agreement, and make broad benefit-sharing more desirable.

Importance of military applications

The military applications of AGI will be more important than the military applications of satellite communications.

The military aspects of satellite communications were significant. Communications satellites were seen to be militarily important for communications in deployment situations and in the event of nuclear war.104 Much of the early research into communications satellites was military,105 and the DoD was influential in the decision to develop geosynchronous commercial satellites, which were preferable for military reasons (see above). Militaries set up their own classified satellite systems, and as an international organization Intelsat struggled to access technical information from military systems because of US ITAR restrictions.106 But in spite of the dual-use nature of communications satellites, Intelsat was successful in establishing a commercial global system.

The general significance of AGI will likely be greater than that of satellite communications, and also the military significance will likely be greater. AGI could provide enormous benefits to intelligence gathering and analysis, strategic decision-making, cyber offense and defense capabilities, drone control, and military R&D.

This poses several problems for the Intelsat for AGI model:

- The US might be less willing to share information and technology which comes with military applications.

- Even if states agreed in principle, it could be legally challenging to share dual-use information internationally.

However, an Intelsat for AGI still seems feasible if membership is limited:

- If membership were limited to Five Eyes countries,107 there would be fewer challenges stemming from trust or information sharing.

- It might be possible to have a small number of founding members who have full technological access, and a larger number of non-founding members, with more limited access.

It is also possible (though far from certain) that developments in AI might make military applications easier to navigate:

- AI might enable robust monitoring and oversight to ensure base models are not used for military purposes.

- If AGI is defense dominant, and/or if strong defensive capabilities are unlocked before strong offensive capabilities, nations might be more willing to agree to share the technology.

The military applications of AGI make a multilateral AGI project more difficult, but an Intelsat for AGI with limited membership still seems feasible.

Degree of government involvement

Governments were more involved in the development of satellite communications technology than they have been so far in AGI development.

The USG developed much of the early satellite technology, via the DoD and NASA.108 And the USG had a monopoly on all launcher technology. European governments were also heavily involved in satellite research via the European Space Research Organization (ESRO).

By contrast, leading AGI development is currently commercial, and almost all GPUs are privately owned.

As well as being more involved in satellite development than AGI development, governments also had a longer history of involvement in telecommunications regulation and governance. Governments had been treating communications networks as a strategic asset for at least half a century, subsidizing infrastructure and negotiating with foreign carriers.109

Governments have been seriously involved in AGI regulation for perhaps one or two years.

There are several reasons to expect that government involvement in AGI development will increase over time:

- The energy and financial requirements for AGI might require state involvement.110

- The military and geopolitical significance of AGI may motivate government involvement.111

- The potential safety risks of AI technology may motivate government regulation or involvement.

- As with satellite technology, concerns about antitrust may motivate government involvement (either to support laggard projects, or to oversee a monopolist).

But it is unclear what the timing of this increased involvement will be, and how far it will counterbalance the relative lack of government involvement so far when it comes to the feasibility of a multilateral project.

Lower government involvement in AGI development so far might make a multilateral AGI project harder to establish and run, unless governments can rapidly hire in expertise from elsewhere.

Degree of dependence on allies

The US depends more heavily on allies for the development of AGI than it did for satellite communications.

The US did need some cooperation from allies to create a global satellite network. In particular, they needed:

- Agreement to reserve radio frequencies for space. Radio frequencies were valuable, and blocks were decided upon by an international body including developing nations, using a one nation, one vote voting procedure.112

- Countries to build or agree to the building of ground stations which were compatible with the global satellite system.113

But technologically, the US did not depend on any allied nations, as it had a substantial lead in communication satellite technology.

In the case of AGI, although the US is the leading developer, it depends on several other countries for key parts of the AGI supply chain. In particular, TSMC in Taiwan and ASML in the Netherlands provide currently irreplaceable parts of the semiconductor supply chain (though this could change if the US developed a domestic industry, or once the US owns enough chips to develop AGI). More generally, key AGI research talent isn’t exclusively American, and it is plausible that some researchers would be more willing to participate in a multilateral project than a US-only project.

Relative to satellite communications, this increases the bargaining power of US allies, and the benefits to the US of forming an agreement. This might make an agreement more mutually desirable: allies will be able to negotiate a more favorable agreement, and the US’s other options are less good. On the other hand, the large disparity in bargaining power between the US and Europe at the time of the original Intelsat negotiations is part of why the negotiations were so fast. With a more even playing field, actors may be more willing to hold out for a better deal, which might slow down negotiations.

Greater US dependence on allies for AGI development could make a multilateral project more desirable, though it might also make negotiations slower.

Future work

In this report, we make the case that Intelsat is a promising (and unusually feasible) model for how a multilateral AGI development project could be set up.

An important strategic question which we don’t address is whether an international project for AGI development is desirable in the first place. To the extent that centralizing AGI development is desirable or inevitable, Intelsat for AGI offers a promising model. But it’s possible that the centralization of AGI development is both undesirable and avoidable, in which case Intelsat for AGI would be moot.

This report also doesn’t propose a concrete vision for how to implement an Intelsat for AGI. There are many important details to work out, including:

- Membership. Wider membership is preferable for representation, particularly if Intelsat for AGI could prove very long-lasting. But narrower membership is far more feasible, especially from a military perspective (see above). What specific membership strikes the best balance here? Should there be a tiered membership structure, with a small number of founding members and a larger number of non-founding members?

- Voting shares. What weighting criteria should be used? What supermajorities should be required for which decisions?

- Enforcement mechanisms. What mechanisms can ensure that members follow through on their commitments? Is it technically feasible to enforce commitments, even in a case where one member gains a decisive strategic advantage?

- Technology proliferation.115 In the case of AGI, it might be highly desirable to share some technologies, to reduce power concentration. But it might also be important to restrict a small class of offense-dominant technologies. How should an Intelsat for AGI restrict the proliferation of dangerous capabilities while encouraging the proliferation of beneficial ones?

We hope that others will take up these questions, given the promise of the Intelsat model.

Conclusion

Any feasible model for international AGI governance needs to be desirable from a US perspective. We think that Intelsat is a particularly feasible model which balances US national interest with meaningful international involvement:

- Intelsat is proof of concept that a multilateral project to build a commercially and strategically important technology is possible and can achieve intended objectives.

- Intelsat shows that a multilateral project can provide major benefits to both the US and its allies compared to the US acting alone.

More specifically, the history of early Intelsat suggests that:

- Weighted voting with supermajorities for important decisions can be politically feasible, giving the US primary control while providing meaningful influence to allies.

- Interim agreements with an initially small number of allies can allow agreements to be set up relatively quickly.

And Intelsat also demonstrates that the formation of a multilateral project provides an opportunity to desirably shape the trajectory that a new technology takes.

Although there are important disanalogies between communication satellites and AGI, we don’t think these undermine the Intelsat model. Greater US dependence on allies and larger benefits both make it easier to reach an Intelsat style agreement. Lower government involvement and more important military applications make Intelsat for AGI harder, but they don’t seem like insurmountable problems.

Intelsat for satellites has faded from significance since its privatization in 2001. Any form of international governance of AGI might have extremely long-lasting significance. We think that Intelsat is one of the most promising models for the scale of this challenge, balancing feasibility with legitimacy.

References

‘Address to Joint Session of Congress May 25, 1961’ (no date). Available at: https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/historic-speeches/address-to-joint-session-of-congress-may-25-1961 (Accessed: 23 September 2024).

‘Agreement Establishing Interim Arrangements for a Global Commercial Communications Satellite System’ (1964), Journal of Air Law and Commerce, 30(3), pp. 264–77. Available at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol30/iss3/4.

‘Agreement Relating to the International Telecommunications Satellite Organization “Intelsat”’’ (1971). Available at: https://csps.aerospace.org/sites/default/files/2021-08/INTELSAT%20Agreement%20Aug71.pdf (Accessed: 23 September 2024).

Armstrong, S., Bostrom, N. and Shulman, C. (2016) ‘Racing to the precipice: a model of artificial intelligence development’, AI & SOCIETY, 31(2), pp. 201–206. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-015-0590-y.

‘AUKUS Defense Trade Integration Determination’ (2024) United States Department of State. Available at: https://www.state.gov/aukus-defense-trade-integration-determination/ (Accessed: 7 October 2024).

Bostrom, N. (2014) Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies. Oxford University Press.

Carlsmith, J. (2024) ‘Is Power-Seeking AI an Existential Risk?’ arXiv. Available at: http://arxiv.org/abs/2206.13353 (Accessed: 20 September 2024).

Codding, G.A. (2019) The Future Of Satellite Communications. New York: Routledge. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429311116.

Collette, R. (1992) ‘Space communications in Europe. How did we make it happen?’, History and Technology, an International Journal [Preprint]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/07341519208581818.

‘Communications Satellite Act’ (1962). Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-76/pdf/STATUTE-76-Pg419.pdf#page=1 (Accessed: 23 September 2024).

Dimitri, N., Gries, T. and Naudé, W. (eds) (2024) ‘Investing in Artificial Intelligence: Breakthroughs and Backlashes’, in Artificial Intelligence: Economic Perspectives and Models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 173–198. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009483094.007.

Doyle, S. (1972) ‘Permanent Arrangements for the Global Commercial Communication Satellite System of INTELSAT’, The International Lawyer, 6(2), p. 258.

Erdil, E. and Besiroglu, T. (2024) ‘Explosive growth from AI automation: A review of the arguments’. arXiv. Available at: http://arxiv.org/abs/2309.11690 (Accessed: 20 September 2024).

Eric Drexler (2018) Paretotopian Goal Alignment. Available at: https://www.effectivealtruism.org/articles/ea-global-2018-paretotopian-goal-alignment (Accessed: 20 September 2024).

Evans, C.E. and Lundgren, L. (2023) No Heavenly Bodies: A History of Satellite Communications Infrastructure. The MIT Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/13771.001.0001.

Finnveden, L., Riedel, C.J. and Shulman C. (2022). ‘Artificial General Intelligence and Lock-In’. Accessed 20 September 2024. Available at: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1mkLFhxixWdT5peJHq4rfFzq4QbHyfZtANH1nou68q88/edit#heading=h.w0odoleyhzrt (Accessed: 23 September 2024).

Fist, T., Datta, A. and Potter, B. (2024). ‘Compute in America: Building the Next Generation of AI Infrastructure at Home’. Available at: https://ifp.org/compute-in-america/ (Accessed: 23 September 2024).

Global Market Insights (2024). ‘Satellite Communication (SATCOM) Market Size’. Available at: https://www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/satellite-communication-market.

Hendrycks, D., Mazeika, M. and Woodside, T. (2023) ‘An Overview of Catastrophic AI Risks’. arXiv. Available at: http://arxiv.org/abs/2306.12001 (Accessed: 6 November 2024).

‘International Traffic in Arms Regulations’ (no date). Electronic Code of Federal Regulations. Available at: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-22/chapter-I/subchapter-M (Accessed 8 October 2024).

Justen, M. (2024) ‘Sharing the AI Windfall: A Strategic Approach to International Benefit-Sharing’, With respect to governing AI, 16 August. Available at: https://wrtaigovernance.substack.com/p/sharing-the-ai-windfall-a-strategic (Accessed: 23 September 2024).

Leopold Aschenbrenner (2024) Situational Awareness: The Decade Ahead. Available at: https://situational-awareness.ai/ (Accessed: 20 September 2024).

Levin, J.-C. and Maas, M.M. (2020) ‘Roadmap to a Roadmap: How Could We Tell When AGI is a “Manhattan Project” Away?’ arXiv. Available at: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2008.04701.

Levy, S.A. (1975) ‘INTELSAT: Technology, politics and the transformation of a regime’, International Organization, 29(3), pp. 655–680. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300031726.

Lipscy, P.Y. (2017) Renegotiating the World Order: Institutional Change in International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316570463.

McDougall, W.A. (1985) The heavens and the earth : a political history of the space age. New York : Basic Books. Available at: http://archive.org/details/heavensearth00walt_0 (Accessed: 10 February 2025).

Nixon, F.G. (1970) ‘Intelsat: A Progress Report on the Move toward Definitive Agreements’, The University of Toronto Law Journal, 20(3), pp. 380–385. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/825227.

Precedence Research (2024). ‘Artificial Intelligence (AI) Market Size, Share, and Trends 2024 to 2034’. Available at: https://www.precedenceresearch.com/artificial-intelligence-market (Accessed: 23 September 2024).

Slotten, H.R. (2022) Beyond Sputnik and the Space Race: The Origins of Global Satellite Communications. JHU Press.

Snow, M.S. (1990) ‘Evaluating Intelsat’s performance and prospects: Conceptual paradigms and empirical investigations’, Telecommunications Policy, 14(1), pp. 15–25. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/0308-5961(92)90106-Y.

Whalen, D. (2014) The Rise and Fall of COMSAT: Technology, Business, and Government in Satellite Communications. 2014th edition. Basingstoke u.a: Palgrave Macmillan.

Appendices

Timeline

Year | Event |

|---|---|

1946 | First DoD satellite plans |

1948 | DoD satellite program scrapped as part of demobilization |

1957 | October: Sputnik 1, first satellite, launched by USSR |

1958 | January: Explorer 1, first US satellite, launched by US NASA founded ARPA and DOD start communications satellite programs December: SCORE, first communications satellite, launched by US |

1960 | Summer: AT&T informs FCC of plans to develop a global satellite system Autumn: Federal agencies begin to consider communication satellite policy First call for government involvement to create a global system for national security reasons, in a staff report commissioned by LBJ |

1961 | January: FCC grants AT&T permission to launch an experimental communication satellite system February: DoJ exempts Lockheed and other companies from antitrust for a joint communication satellite project 12th April: Yuri Gagarin, first man in space 14th April: Kennedy asks aides how to win the space race 17th-21st April 1961: Bay of Pigs 25th May: JFK gives a speech to Congress, committing to a man on the moon, and a global communication satellite system Special Commonwealth Conference on Satellite Communications in London. Canada and the UK instructed to discover US intentions |

1962 | July: Telstar 1, first live TV from a communication satellite August: The Communications Satellite Act establishes the Communications Satellite Corporation (Comsat) September: first international discussions, with the UK and Canada and at their request October: Cuban missile crisis |

1963 | May, July, November: intergovernmental meetings between European powers on whether and how to join the American system. They direct their steering committee to negotiate with the US. The committee invites the US and Canada to an exploratory meeting in Rome |

1964 | February: exploratory meeting in Rome between US, the European bloc, and Canada/Japan/Australia (at US insistence) June: Comsat IPO raises $200 million July: final negotiations in Washington DC August: Agreement Establishing Interim Agreements for a Global Communications Satellite System signed |

1965 | Intelsat launches first satellite, Early Bird NSAM 338 prohibits the launch of non-Intelsat communications satellites in the US |

1967 | NSAM 338 reissued |

1968 | Invasion of Czechoslovakia Intersputnik proposed by the USSR December: ICSC submits its report on alternatives for the definitive agreements |

1969 | February to March: First Plenipotentiary Conference. Established a Preparatory Committee to reduce the number of alternatives June/July, September, November/December: Preparatory Committee meetings Intelsat achieves world coverage (Pacific, Atlantic, Indian Ocean basins) |

1970 | February to March: second plenipotentiary conference May/June, September/October, November/December: International Working Group drafts definitive agreements December: IWG submits draft agreements to the final conference |

1971 | April: Final Conference begins May: Final texts of the agreements passed August: Agreements opened for signature |

1972 | Intersputnik comes into force First domestic communications satellite launched in Canada December: 2/3 of members signed definitive agreements |

1973 | February: definitive agreements enter into force |

1974 | France and Germany launch Symphonie regional satellite using a US launcher First US domestic communication satellite |

1977 | CEPT signs interim EUTELSAT constitution agreement |

1979 | ESA develops Ariane, first European launcher End of Comstat’s term as manager of the Intelsat system |

1982 | INMARSAT, maritime satellite system, founded EUTELSAT becomes first operational regional satellite system |

1983 | First Eutelsat satellite launched US companies apply to compete with Intelsat in international communications satellites |

1984 | Reagan permits competition with Intelsat |

1985 | EUTELSAT definitive agreement comes into force |

1988 | First transatlantic fiber-optic cable |

1998 | 5 satellites spun off to Dutch company New Skies Satellites, to compete with intelsat |

2001 | Intelsat fully privatized U.S. Congress passed the Open-market Reorganization for the Betterment of International Telecommunications (ORBIT) Act to privatize COMSAT |

Lead times

US | USSR | Europe | |

|---|---|---|---|

First satellite | 1958 (Explorer) | 1957 (Sputnik) | 1962 (Ariel; UK) |

First communications satellite | 1958 (SCORE) | 1965 (Molniya) | 1974 (Symphonie; Germany and France) |

First satellite launcher | 1958 (Explorer) | 1957 (Sputnik) | 1979 (Ariane; ESA) |

First TV | 1960 (Echo) | 1965 (Molniya) | 1974 (Symphonie; Germany and France) |

First live TV | 1962 (Telstar) | 1965 (Molniya) | 1974 (Symphonie; Germany and France) |

First global satellite system | 1964 (Intelsat) | 1971 (Intersputnik) | 1964 (Intelsat) |

Footnotes

Released on 13th March 2025